This Book Will Make You Kinder: discover your own special superpower

A simple guide to empathy and compassion: two traits we all could use more of

Right when it came out, I read ‘This Book Will Make You Kinder’. I have been following the Instagram account @henryjgarrett for years and was very excited when Henry James Garrett, the person behind the account, announced that he would be writing a book. I expected it to be a wholesome book about empathy, kindness and witty cartoons of animals and objects. It was so much more.

After reading ‘This Book Will Make You Kinder’, I felt very inspired. I wanted to give it to everyone I knew so they could also learn what it means to be kind, and actually exercise our empathy muscles to become even kinder.

The book gave me a sense of ‘calm’ that I hadn’t experienced before. Because I hoped that everyone who read the book, would want to work towards a kinder world. To do everything in their power to switch on their empathy to make the world a better place. And to always choose kindness in their day-to-day interactions.

I already knew this book would be a very wholesome and satisfying read. It did not disappoint. It also provided me with a bunch of new things to feel anxious about but… totally worth it.

(A little side-note: if you choose not to read this book or even this review of the book, you are making an empathy limiting mistake. The title literally says it will make you kinder and you consciously choose the easier, comfortable, less confronting option of not reading it. With that you are choosing not to expose yourself to possibly harsh truths but also the ability to be better and do better. See how I paid attention in class?)

Short summary for quick readers

- This Book Will Make You Kinder revolves around empathy and morality: your reasons for being kind determine how kind you can and will be.

- Everyone has a personal threshold for 'kind enough'. A lot of people base this threshold on the law or religion but that's the bare minimum according to Henry James Garrett.

- Unkindness is usually easier than kindness: a low effort choice. Especially in a world where the bare minimum – based on laws and religion – is considered 'kind enough'.

- It is important to recognize opportunities to be kind whenever they present themselves. According to the book, we all have an empathy off-switch. One that we switch off when we've hit the (according to us) bare minimum of kind.

- Especially since we usually extent empathy to people in our in-group, not our out-group. And that makes us less kind towards certain groups of people.

- The book differentiates between culpable and inculpable ignorance: not knowing and knowing but choosing the wrong thing despite knowing.

- Cognitive dissonance occurs when we make unkind choices (culpable ignorance): we make up excuses why it is justified that we choose to look away.

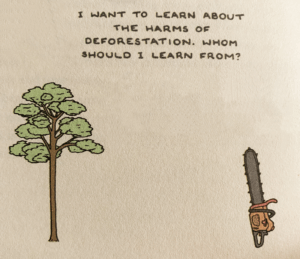

- The key to fighting all this is listening and being open to people from the groups that are being harmed. And listening isn't a character trait that you just 'have' or don't have. It is an action that everyone can do.

- To listen means to hear them. Listening means taking the information and implementing it and using that information in the future. To look or look away; it's that simple.

* Free wallpaper download * Free wallpaper download * Free wallpaper download

* Free wallpaper download * Free wallpaper download * Free wallpaper download

Empathy and morality

The book revolves around the concept of empathy and how empathy is the basis of morality.

To clarify that, Henry writes about the motivations we have for being kind and why these motivations matter. Because your reason for being kind determines how kind you can and will be.

Morality is usually a very personal thing: what you think ‘kindness’ means and when you feel like you’re meeting your own threshold for ‘kind enough’, is personal. Many people base their threshold off of the law or religion or what they learned growing up. But when things like ‘Thou shalt not kill’ are the basis of your moral compass, then it is fairly easy to be kind.

I think (or hope) that the majority of the people can easily say they have never killed anybody or stolen anything. They have followed the rules of their religion or followed the law. Does that make them as kind as they could be though?

Henry disagrees. And so do I.

Kinder is harder

According to the book, empathy is the basis of morality because it makes us act without ulterior motives. When I think about my own ongoing journey with kindness, I would agree.

In so many cases where I am provided with a choice between kindness or unkindness, the latter one is usually the easiest option. Being unkind in a world where the bare minimum is considered “kind enough”, is the comfortable choice.

Imagine a scenario in which your friends start gossiping about a person they know. They make fun of the way they look and wait for you to pitch in. You are provided with an opportunity to be kind here (just to be sure we are all on the same page, the kind option would be to not gossip. Gossiping is considered unkind). The very easy and comfortable option would be to just go along with it and gossip with them. You will still be that “fun” friend and not the “buzz-kill queen of morality”.

So, if the only reason for us to empathize with people is selfishness or following the rules, then why doesn’t it feel good to go along with your friends? The law says nothing about gossiping, we would not be breaking any rules.

And yet, we know it is wrong.

What I think is important is that we recognize the opportunity to be kind whenever it presents itself and think about why we would choose one option or the other.

Turn on your kindness

According to Henry James Garret, empathy has an off-switch. And we make a lot of mistakes – sometimes even choices – switching our empathy off at a time where we should actually leave it ‘running’. Being kind by following the rules is one of those things that triggers the off-switch: when we have made the choices necessary to follow the rules, we have met our own threshold for being kind and can pack up for the rest of the day.

But rules do not provide context.

The bible is often misinterpreted or interpreted differently by many people. So how do we know those rules are what is needed to be ‘kind enough’? Another question to ask is: Who made these rules in the first place?

Do the rules benefit all people, or only a certain group of people?

Kinder to our ‘in-group’

The book is an ode to empathy. Empathy is defined as the ability to understand and share the feelings of another. The book provides a little bit of information about the evolution of empathy

(To me, as a non-native English speaker it got a little blurry at that point but hooray for cartoons to clear everything up).

Evolution gave us the ability to empathize with what we know. We empathize with our “in-group” because that is what we know. This also means that we can expand our empathy if we expand ‘what we know’.

When we broaden our horizon of knowledge; actually listen to other people with different experiences, we can empathize with people that we do not yet understand. We can empathize with the “out-group” and actually turn them into an “in-group”.

Our empathy is limited by our beliefs, making us less kind to certain groups of people. That’s because we do not know enough about them. When you have a hard time understanding trans people, you will view them as “different” and you will not understand them. You won’t empathize with them and when a law gets passed that excludes trans people, you will not feel any need to help them.

But when you actually take time to listen to trans people, you will hear about the many troubles they face going about life and how hard many seemingly “ordinary” things can be for them. This applies to all people different from you. Black people, POC, people from the LGBTQ+ community, people with a disability, fat people, etc.

Everyone deserves kindness, just like you do.

Excuses for unkindness

The book differentiates between culpable and inculpable ignorance. Inculpable ignorance is ‘not knowing’, culpable ignorance is knowing, but choosing it all the same.

You can guess which one of these two is worse. If you do not know you are causing harm, then the only thing you can do is listen and do better next time. If you do know you are causing harm but you choose to ignore it, then you are actively choosing to be unkind.

We jump through hoops to justify our unkindness.

We deny everything just so we do not have to face our complicity: ‘People are not suffering and if they are, they are not suffering because of me’. Culpable ignorance is the comfortable option, it is the easy way out. In psychology this can be described with the term ‘cognitive dissonance’: we know that our actions do not match our moral standards so our brain does everything in its power to change the standards and think of excuses why what we are doing is still OK.

Buying unsustainable fashion despite knowing it is bad for the environment is an example. We buy new sneakers from companies we know treat their employees poorly but we wave it away.

Choose discomfort

It is very confronting to think about the ways in which you have done other people harm. And I know it is much easier to just let your mind come up with excuses why it is OK: ‘Well, if I do not buy from this company, those employees get nothing so that is not an option either…’

People like to hide behind excuses to justify unkindness.

One of the excuses that the book mentions is how a kind world would be unrealistic. A world without suffering would be unrealistic and that is why we should not aim for it. This is again, the comfortable option.

Nothing has to change because nothing can be done.

I do not actively have to do anything different from what I was doing. But how do you know if a kind world is unrealistic, if we have never actually tried to built towards it? Kindness so far has not been the foundation of humanity in our society.

We have mostly been working toward selfishness and fending for ourselves. So who knows if it would work? I would love to find out. I would prefer a kinder world over any other option, wouldn’t you?

Listening is kinder

The most important takeaway from this book for me is that the key to all of this is listening.

‘If ignorance is poison, listening is the only antidote’.

One thing the book is pretty clear about is that listening is not a character trait. To categorize listening as a character trait, changes it into something we either do or do not ‘have’. And if we do not ‘have’ it, we do not have to do it. ‘I am just not a good listener’ is a very sorry excuse for unkindness (and it kind of makes you a shitty person).

But everyone is able to listen in some way. We have to listen to people with different points of view from our own. To voices that are never amplified.

The people who are always labeled as ‘too much’ of anything.

Black people, POC, women, disabled people, trans people, gay people; people who almost never get a platform to speak about the things that hurt them. Those are the people we should listen to. Why? Because their experience matters just as much as all the experiences we see in the papers. All the voices that never actually get to speak for themselves? Their stories get told for them by journalists, scientists, celebrities, the news, etc. It is time to actually hear what they have to say themselves.

To illustrate that point, I added one cute drawing from the book that sums it up perfectly.

The drawing is by Henry James Garrett (@henryjgarrett)

Choose kindness

And to really listen to someone, means to actually hear them.

It means to open up and actually welcome a new point of view. Do not listen just to debunk the story. Do not listen because you want to confirm you are right. Do not listen just so you can hear what you want to hear and add it to your list of ‘reasons not to choose kindness’.

If you practice listening, it means that you actually take the information someone gave you and implement it in your own little database of ‘what we know’.

To quote the book one last time: ‘To look or look away’. It is that simple.